As anyone who has been studying wushu for longer than a week can tell you, the most common question any of us hear (almost on a weekly basis) is “What is wushu?”

The problem with this question is that it is a bit like trying to describe color to a blind person. Wushu is a vast and diverse system/philosophy with far more depth than can possibly be explained in a casual conversation.

Of course, most of us just end up saying “Chinese Martial Arts” or “Kung Fu“, neither of which is terribly helpful, and both of which just lead to more questions.

So, in my effort to alleviate this issue for myself (and maybe some of you), I’ve written up this introduction to wushu, in the hopes that after reading it, folks will have a better grasp of what wushu is — and more importantly, what wushu isn’t. (For example, it is not a Chinese pork dish — that joke is to wushu people what lawyer jokes are to law students.)

So, what is wushu? (The answer may surprise/bore/annoy you!)

Literally wushu is a Chinese word, 武术 (武術, in traditional Chinese characters), which is a combination of the characters wǔ, which means “martial“,”war” or “combat“, and shù, which means “art form“. So, wushu literally means “martial arts“.

Now, the problem with such a generic definition is that you can actually use wushu to describe a whole range of martial arts.

In fact, technically, all martial arts — from karate to kali, capoeira to boxing, fencing to wrestling — could be called wushu. They are all combat arts which require a refined skill and physical artistry.

Sometimes when I tell someone in China that I study wushu, they even ask me “Chinese Wushu? (中国武术?)”, just to confirm which general type I practice.

Now, again, the problem with this definition is that since Chinese martial arts originated thousands of years ago, you have had a lot of spreading of Chinese martial arts to non-Chinese locations. In fact these days pretty much all martial arts in Eastern Asia owe a strong chunk of their original lineage to China. Karate, tae kwon do, aikido, jiu jitsu, etc., all originate from Chinese origins.

But just like General Tso’s Chicken or Fortune Cookies in the U.S., things that leave China tend to take on a life and identity of their own.

I think that most people ignore this fact when saying “Chinese martial arts“, preferring to think of wushu as the styles and forms of martial arts that still retain their Chinese cultural and social roots.

I guess the general rule most people follow is, if the name of the style is still said in Chinese, then it is Chinese wushu.

For example, most people wouldn’t say that choy li fut (蔡李佛 or cài lǐ fó) isn’t Chinese, even though it is probably practiced by more people outside of China than inside. But once you call a style by another name, “kenpo” for example, (which is a Japanese word originating from the Chinese, 拳法 (quán fǎ), meaning “fist method“), then it takes on other meanings and cultures.

Of course, like anything that is thousands of years old, you will have a lot of variations and divisions and splintering factions of wushu. Just like Latin-based languages have divided themselves into countless variations of linguistic diversity, so too has wushu become a tree with both a strong trunk and foundation in the past, but also endless branches and fruits which go in to the present time.

Internal vs. External

One of these divisions is between internal and external styles of Chinese martial arts.

As a (gross) generalization, internal wushu are styles that focus on breathing, qi (energy) development, and cultivation of inner skill or power (called 內功, nèi gōng).

Of course, this is sort of a strange distinction since all styles of martial arts essentially talk about the importance of qi, breathing and inner power. It isn’t like practicing an external style means you no longer care about your breathing, right?

And on the other side of the coin, external styles are usually those that focus on power, strength and exertion of outer force (called 外功, wài gōng).

Which is also strange because both external and internal styles focus on developing power, strength and being able to exert force.

So, what is really the difference between internal and external martial arts?

I suppose it comes down to a matter of focus. While both emphasize aspects shared by all martial arts, certain styles focus their attention on certain areas more than others.

For Chinese wushu, most people consider there to be 3 main schools of internal Chinese martial arts:

- 1.太极拳, tài jí quán (sometimes written tai chi ch’uan)

- 八卦掌, bā guà zhǎng (sometimes written pakua chang)

- 形意拳, xíng yì quán (sometimes written hsing yi ch’uan)

(Some day I’ll tackle the whole Wade-Giles vs. Pinyin romanization of Chinese, and how it’s made understanding Chinese martial arts that much worse for the general population. But for now let’s just go with the Pinyin spelling, okay?)

In this case, popularity is the name of the game, and the “main styles” are so named because they have the most people practicing them.

I always find it interesting when I tell someone I practice wushu and they say “I’ve never done wushu, but I took Tai Chi for a while“. Clearly they don’t realize that they just said the martial arts equivalent of “I’ve never danced before, but I studied the Cha Cha for a while“.

However, it is true that, in some people’s mind, internal styles of Chinese martial arts are not a part of “wushu“. They have a narrower definition of wushu, delegating other branches of the martial arts tree to this term.

Unfortunately, even within the “external” styles of Chinese martial arts, there is another division which vies for wushu’s identity as a comprehensive term.

Kung Fu vs. Wushu

We can thank Bruce Lee for this one.

He introduced the term “kung fu” (or 功夫, gōng fu) to the West without explaining the literal translation.

Kung fu does NOT mean “martial arts“. It is not even a style of martial arts.

In fact, kung fu doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with martial arts.

(That’s right. I said it.)

It is a term that refers to a specific level of mastery in a skill. In essence “kung fu” means “super high level skill which results from lots of effort exerted over time“. (Say that 10 times real fast!)

Which is why I’ve always found it strange when people say “I practice kung fu” because literally that means “I practice mastery“, which, honestly, tells me almost nothing about what you do. Heck, people on So You Think You Can Dance practice kung fu, if you look at it that way.

Yes, I’m being a little facetious. But it is still a valid point to make.

Of course, society, language and time have a way of changing the meanings of words. For example, “awesome” is no longer something that is actually the inspirer of “awe“. It has come to mean something else in today’s vernacular, even though it still maintains some of it’s original meaning.

Likewise, “kung fu” has come to be associated with Chinese martial arts, usually of the traditional variant. (More on that later.)

And if you’re going to associate the term “kung fu” with Chinese martial arts, then at some level the term becomes synonymous with “wushu“, which also means “Chinese martial arts“.

So then, what is the difference between kung fu and wushu?

And unfortunately that really depends on who you ask.

Some will say there is no difference. Kung fu and wushu are both the same thing.

Others will say that they are completely different and kung fu and wushu have barely any relationship with each other.

And there are those in the middle that will say that kung fu and wushu are just two aspects of the same thing — two sides of the same coin.

But here is the thing …

A person’s answer to the question about the difference between kung fu and wushu doesn’t actually tell you what the difference is — it tells you who the person is. Or specifically, what that person believes.

Because when someone gives you an answer that runs anywhere across that spectrum from “totally different” to “totally the same“, they are really saying more about themselves than about martial arts.

They are telling you who THEY are and what their relationship with martial arts is.

People answer questions based not on the truth, but on their perceptions.

Because the truth to the answer “what is the difference between kung fu and wushu?” is “it depends on how you define those terms“.

And anyone who gives you some other answer is telling you, not what the difference is, but they are telling you their personal definitions of the terms “kung fu” and “wushu“.

This sort of thing used to annoy me, because I have a pet peeve about people forcing their personal opinions and definitions on to other people. But, now I just accept it as part of the way things work. If nothing else, it gives us something to talk about when we are standing around in a parking lot after wushu practice, right?

So, after having said all of that I am still going to give you a generalized answer. (Yes, I know … Total. Hypocrite.)

But y’know, even though many people might have their own personal take on the situation, a fair majority of people tend to use kung fu as a term that refers to “traditional” styles of Chinese martial arts, and wushu to be a term that describes “contemporary” or “modern” styles of Chinese martial arts.

But, of course that just brings up a whole new question …

Traditional vs. Modern

Yet another branch on the tree of martial arts is that between “traditional” and “modern” Chinese martial arts.

This is where you start to get in to a bit of history. You see, the reality is that ALL forms of martial arts were once considered “modern“. Who ever first came up with Praying Mantis style was probably considered way-the-heck-out-there to the other martial artists of the day.

A: “What do you mean you saw a mantis fighting another insect and decided to create a style of wushu around it?”

B: “No, seriously man. Check it out. I’m way better at fighting when I pretend I’m a bug.”

A: “… weirdo.”

The martial artist that decides that theirs is the only style worth knowing, and that it need not develop any farther, is someone who has closed their mind and cut off their development.

They are like the painter who decided that Picaso was the pinnacle of painting, only copying that style and deeming any further creative exploration of painting as worthless.

Whatever you might see as “modern” (or strange) today will someday be considered “traditional”. In fact, that is already happening.

People today consider the 70’s version of contemporary wushu to be very different in it’s approach. No one really does it like they did in the 70’s, and so that is seen, at least to some degree, as being a bit “traditional“.

(Of course, we don’t use the word “traditional” since it is already used with a specific meaning in the martial arts community, so most of us just say “old school“.)

So, wushu, as an art form, is constantly evolving. And that evolution usually mirrors the needs of the people who practice it in any given time.

Survival of the fittest

A super long time ago wushu was a method for keeping monks from being too sedentary. It was for physical vitality and health so that a spiritual path could be pursued. Survival in that context required that wushu (or whatever name they used at the time) was used as a method to maintain the strength and energy for one’s spiritual endeavors.

Then, a while after that, wushu became used for battling other people. The world was a rough place, and so survival in this world was about protecting yourself and your kin. They developed bare-handed methods of fighting. They made weapons — swords, sticks and spears — creating systems to use them effectively. It was an evolutionary process, and each generation that practiced these art forms improved upon them changing things here or there — sometimes changing them in completely unrecognizable ways — in order to better suit the needs at that time.

And, as you well know, in history the greatest amount of change in society and culture has happened over the past 200 years.

Since the 19th century things have been changing at an unprecedented rate. It is only natural, therefore, that wushu and martial arts would change too. If the creative arts are a reflection of the society, culture and times they exist in, then wushu is no exception to that rule and must also reflect societal changes.

Unless you have been living under a rock, then you probably know that China experienced quite the socio-political upheaval during the middle of the 20th century.

A lot of people left China and they took their wushu with them.

Some people stayed in China and kept practicing in private.

This geographic division also promoted another division in the development of wushu.

Don’t call it a comeback …

By the time the inner turmoil in China started to subside, the people in charge realized that certain elements of Chinese traditional culture and art could be beneficial to the people.

But instead of focusing on the elements of wushu that cause trouble — the application of fighting techniques — they decided to promote the parts of wushu that promote their culture — the aesthetics of fighting movement.

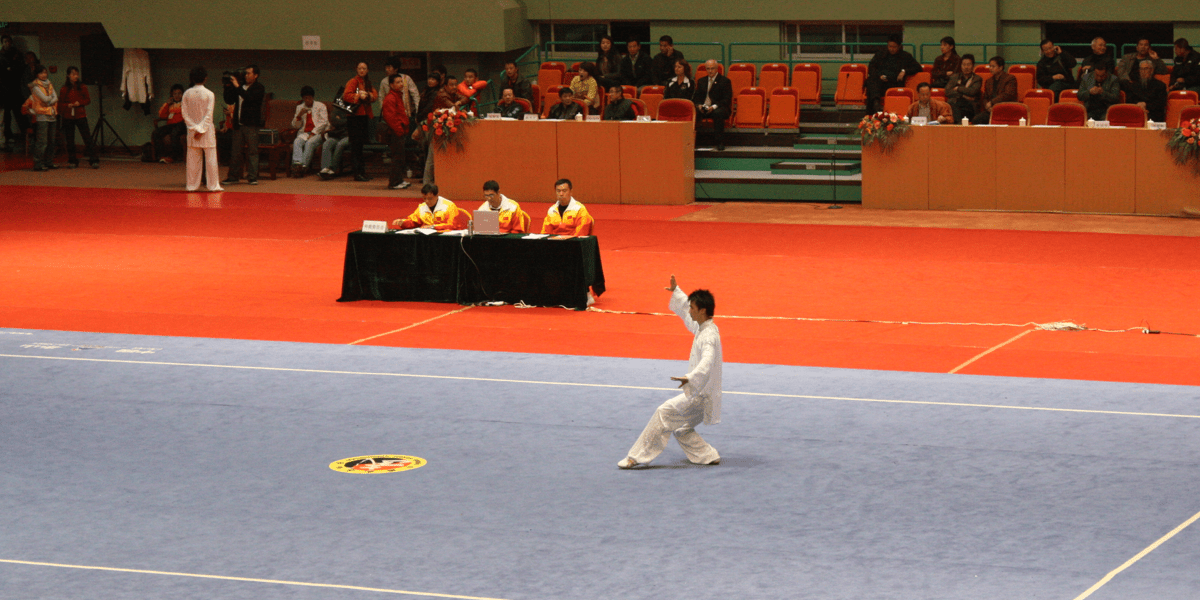

And, since it was a physical endeavor to train in wushu, it joined the ranks as a competitive sport.

In the beginning, those that first developed the sport-focused variant of wushu worked hard to maintain it’s martial roots.

Many of the new, young athletes who studied with more traditionally minded masters had to learn entire systems of application — in the way the styles had been taught for generations — before focusing on the aesthetic performance of forms. Traditionally forms were a way by which you remembered application, not the other way around.

That’s right. The early wushu athletes had to learn how to fight before they could learn their forms. Hard to imagine, isn’t it?

But over time, this focus on application waned. Not because application isn’t important. (Ask any contemporary wushu athlete and they will tell you that, without understanding the application, forms are completely empty.) It is because application was no longer the criteria upon which you were rewarded (and survived) in wushu.

Ultimately wushu, like most things in life, is a matter of reward and punishment for certain types of actions and behaviors. You get rewarded by society/people/life if your skill applies to survival in certain contexts.

Since an athlete’s survival depends on receiving specific scores based on specific criteria, then that is the context under which their wushu develops. Whatever criteria they must thrive under, is what dictates the direction that wushu will take.

A wushu practitioner’s survival no longer depends on defending themselves from, or being in life-or-death combat with, other people. It now depends on jumping high, looking amazing and having incredible speed, power and artistry. That is the reason that modern sport wushu has developed in the way it has, and also the reason why many traditional styles have changed too.

If things in society changed such that wushu athlete’s were rewarded by being able to defend themselves in hand-to-hand combat, then you can be sure that the emphasis for contemporary wushu practitioners would change dramatically.

Wushu as a contemporary sport has gone through a lot of changes over the years. And there are a lot more divisions that exist within it — changes that are too numerous to describe in full here.

From sanda vs. taolu, to contemporary-traditional vs. contemporary-modern, to northern vs. southern, to long weapons vs. short weapons to … well, you get the idea.

A survey of contemporary wushu is a topic best left for another day. Sufficeth to say, contemporary sport wushu is a vast area that is definitely worth further discussion.

Traditional wushu’s evolution

Meanwhile, back in the middle of the 20th century, those who had left China and maintained their traditional focus on application as the primary expression of their art, found themselves in a strange situation not too different than those inside China.

As society evolved and people matured, man-to-man combat (or woman-to-woman as the case may be) was no longer considered an acceptable way to resolve a conflict.

Around the same time that wushu inside China found it’s survival dependent on athletic performance, wushu outside of China found it’s survival dependent on aspects of life not focused on combat.

So, what happens when you have an art with combat as it’s foundation finds itself in a world where the highest expression of your art form is no longer socially acceptable?

You adapt, of course.

But it was an adaptation that wasn’t easy. People cling to their traditions and innovation often takes several generations. Plenty of people are still adapting today. It is only natural, really, and in the end probably not such a bad thing.

Many teachers who had focused on the application of martial arts realized that martial arts could be used for other methods of survival.

Instead of surviving by defending themselves or fighting others, they could survive by teaching and passing on cultural heritage to another generation.

“But wushu master’s have been teaching to pass on their cultural heritage for a long time already“, you might say.

True, this sort of thing wasn’t necessarily new, but as mankind continued it’s social maturity, and use of martial arts in combat became less and less common or necessary, this transition increased in pace.

It became less about teaching martial arts so that your students could survive a conflict — you taught martial arts so that your art could survive social changes. Teaching, and getting paid to teach, is a way of surviving in today’s society, which is just as legitimate as defending your village against marauders hundreds of years ago.

The state of wushu today

So, these days you have one segment of society that utilizes it as a method for survival through athletic sport performance — the “modern wushu athlete“.

And you have another segment of society that utilizes it as a method for survival through cultural arts education — the “traditional kung fu master“.

And there are a whole range of people in between. But the part of society that still uses wushu as a means of surviving through combat is incredibly small.

Does that mean wushu (however you define it) isn’t worth studying if you never have a chance to use it?

Certainly not.

Like all arts, wushu is more than just a means to a specific end. There are more facets to the study of martial arts than can possibly be listed here.

From the physical health aspects, to the spiritual cultivation, to the development of specialized skills used in other sports, acting, other arts, education, the uses and implementation of a martial arts education are countless.

As anyone who has studied martial arts for a length of time can tell you — martial arts isn’t about conflict, even though it is a system based on combative techniques.

I realize that to most people that sounds oxymoronic.

I’ve been in more than one discussion where people were adamant that martial arts are only about fighting and that people who trained in martial arts hundreds of years ago didn’t do it for personal development — they did it to beat up people so they wouldn’t get killed.

But that is the point, isn’t it? This isn’t hundreds of years ago.

No one is going in to your town to pillage your treasure and steal your cows. In today’s society the purpose of martial arts has become elevated.

Just like music that was once used as a way to pass on oral tradition and history through society, but is now used for everything from therapy to communicating with animals to artistic expression to combating illness.

Wushu has also come from a specific background and developed in to something that is much more than it ever was before.

So, what is wushu?

In the end the answer to the question “what is wushu” — at least the only answer that a person can give with any accuracy — ends up being the most unfulfilling answer a person can hear:

“It depends“.

Perhaps it will help to think of this in a different context …

If an intelligent robot with no emotion asked you “what is love?” how would you describe it? Would you have an easy answer?

Love is defined by those who feel it.

When you feel it, you know it. And it can be felt in so many different ways by so many different people that there is not one single answer that would satisfy all who experience it.

Wushu is also defined by those who practice it.

When you study it, you begin to understand it. But you understand it in a way that is unique to you, your teacher, your life and your environment.

Because there is no single answer that will satisfy all the people who practice wushu.

To completely change a popular expression, wushu is as wushu does.

And if you are one of those who “does” wushu, then however you define it for yourself is really the only definition you ever need to worry about.